Aquatic Invasive Species

High Mercury Levels in Fish Linked to Zebra Mussel Infestations in Minnesota Lakes

Published Winter 2025

Minnesota is grappling with a troubling environmental issue: the rise of mercury levels in fish from lakes infested with zebra mussels. This invasive species, originally from Eurasia, has spread rapidly across North America, significantly altering aquatic ecosystems. Recent studies suggest a disturbing connection between zebra mussel infestations and elevated mercury concentrations in fish, posing risks to human health and the environment.

Zebra Mussels and Their Impact on Ecosystems

Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) were first discovered in Minnesota in the late 1980s and have since invaded many lakes and rivers. These small, filter-feeding mollusks are notorious for their ability to outcompete native species and disrupt food chains. They filter vast amounts of water, removing plankton and other particles, which has cascading effects on aquatic ecosystems.

By filtering water so effectively, zebra mussels increase water clarity, allowing sunlight to penetrate deeper. This promotes the growth of aquatic plants and algae, which can lead to oxygen depletion and changes in fish habitats. However, their impact goes beyond these visible changes; they also play a role in altering mercury dynamics in lakes.

Mercury in Lakes: A Persistent Threat

Mercury is a toxic element that accumulates in aquatic systems primarily through atmospheric deposition. Once in the water, mercury can be transformed by bacteria into methylmercury, a highly toxic form that bioaccumulates in the food chain. Fish at the top of the food web, such as walleye and northern pike, often have the highest mercury levels.

Studies have shown that zebra mussels can influence mercury cycling in lakes. By altering the food web and increasing algal blooms, they create conditions that may enhance the production and accumulation of methylmercury. Additionally, zebra mussels themselves can concentrate mercury, which then becomes available to other organisms through predation.

Evidence from Minnesota Lakes

Recent research conducted in Minnesota has revealed a concerning trend: lakes with zebra mussel infestations often have fish with higher mercury levels compared to non-infested lakes. For example, in some infested lakes, mercury concentrations in popular game fish have exceeded safe consumption limits set by the Minnesota Department of Health. This has raised alarms among anglers and public health officials alike.

The relationship between zebra mussels and mercury levels is complex and influenced by various factors, including lake size, water chemistry, and the extent of infestation. However, the evidence suggests that zebra mussels exacerbate the problem of mercury contamination in fish, adding another layer of concern to their ecological impact.

Implications for Public Health and Policy

High mercury levels in fish pose significant risks to human health, particularly for pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children. Consuming fish with elevated mercury can impair neurological development and lead to other health issues.

To address this issue, Minnesota officials are ramping up efforts to prevent the spread of zebra mussels and monitor mercury levels in fish. Anglers are urged to follow fish consumption advisories and report any sightings of zebra mussels in uninfested lakes.

Moving Forward

The link between zebra mussels and mercury contamination underscores the need for comprehensive management strategies to protect Minnesota's lakes. Public education, stricter regulations on boat cleaning, and continued research into the ecological impacts of zebra mussels are critical.

As Minnesotans enjoy their lakes, they must remain vigilant in safeguarding these natural treasures. Tackling the dual threats of invasive species and mercury contamination will require collaboration among scientists, policymakers, and communities to ensure the health of both the lakes and the people who rely on them.

Sources JAN 2025: ChatGPT, StarTribune, MAISRC, MPR.

The Big Problem with

Curlyleaf Pondweed

Published Spring 2025

Curlyleaf pondweed (CLP) is an invasive plant that has spread across over 700 Minnesota lakes – including Lake Independence. It has curly, wavy leaves and can grow up to 15 feet tall.

This plant can cause significant problems for the environment and recreational activities in our lakes. CLP aggressively displaces native aquatic vegetation, thriving in early spring when most native species are still dormant. By early summer, the plant dies back—unlike native vegetation that dies off in the fall—releasing large amounts of phosphorus into the water. This nutrient release is a major trigger for toxic blue-green algal blooms, which cloud the water, reduce oxygen levels, and can result in beach closures and harm to aquatic life

Also, thick mats of curly-leaf pondweed can get tangled in boat propellers, fishing lines, and make swimming unpleasant. It covers large areas of the lake, making it hard to enjoy activities like boating, fishing, and swimming.

There are many management strategies to control CLPW, mechanical harvesting, chemical treatments and scientists are looking into using natural predators, like certain types of insects, to control curly-leaf pondweed but this method is still being researched and is not widely used yet.

We are preparing to take action on Lake Independence with a 5-year plan to control CLPW. Attend LICA’s Annual Meeting on April 26th to find out more information.

Here are some recent case studies and research findings on curly-leaf pondweed (Potamogeton crispus) and its association with algal blooms:

1. Gleason Lake, Minnesota (2007–2013)

A comprehensive study in Gleason Lake evaluated the effects of early-season endothall herbicide treatments over seven years. The treatments effectively reduced curly-leaf pondweed abundance. Interestingly, as curly-leaf declined, coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum) proliferated, potentially contributing to improved water clarity and reduced phosphorus levels. However, the study noted that while water transparency increased, the reductions in phosphorus and chlorophyll-a were not statistically significant. University Digital Conservancy+2Taylor & Francis Online+2University Digital Conservancy+2

2. Lake Osakis, Minnesota

Lake Osakis has been grappling with curly-leaf pondweed infestations for decades. The Osakis Lake Association estimates that managing this invasive species costs approximately $200,000 annually. The pondweed not only impedes recreational activities but also contributes to algal blooms by releasing nutrients upon its mid-summer die-off. Alexandria Echo Press

3. Bass Lake, Plymouth, Minnesota

In 2020, the Shingle Creek Watershed Management Commission initiated treatments in Bass Lake to control curly-leaf pondweed. The strategy involved early-season herbicide applications followed by alum treatments to bind phosphorus in the water column. This integrated approach aimed to curb algal blooms by reducing nutrient availability. CCX Media

4. Belgrade Lakes Watershed, Maine

In 2022, curly-leaf pondweed was identified in the Belgrade Lakes Watershed, marking a significant ecological concern.Local organizations, including the 7 Lakes Alliance, collaborated with state agencies to assess the infestation's extent and develop management plans. Public awareness campaigns emphasized preventing the spread to other water bodies. 7lakesalliance.org

5. Research on Native Macrophyte Assemblages

A study by Ajay Robert Jones (2010) investigated the impact of repeated early-season herbicide treatments on native aquatic plant communities in Minnesota lakes. Findings indicated that while curly-leaf pondweed was effectively controlled, native plant species richness and biomass showed minimal changes, suggesting that multiple years of treatment might be necessary to observe significant ecological shifts. University Digital Conservancy+1University Digital Conservancy+1

More resources about Curlyleaf Pondweed:

1. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Provides information on identification, impacts, and management strategies.

Contact: Invasive Species Program

Phone: (651) 259-5100

Website: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/invasives/aquaticplants/curlyleafpondweed/index.html

2. Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center (MAISRC)

Researches distribution and control of curly-leaf pondweed.

Phone: (612) 626-1412

Website: https://maisrc.umn.edu/curlyleaf-pondweed

3. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Offers species profiles, fact sheets, and management tools.

Contact: DNR Invasive Species Program

Phone: 1-888-936-7463 (TTY: 711)

Website: https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/Invasives/fact/CurlyLeafPondweed

4. Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks

Monitors and manages aquatic invasive species.

Contact: Emporia Research Office

Phone: (620) 342-0658

Website: https://ksoutdoors.com/Fishing/Aquatic-Invasive-Species/Aquatic-Invasive-Species-List/Curly-Leaf-Pondweed

5. Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP)

Provides prevention and control guidance for aquatic invasives.

Phone: (207) 287-7688

Website: https://www.maine.gov/dep/water/invasives/curly_leaf.html

6. National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC)

National clearinghouse for invasive species information.

Phone: (301) 504-5547

Website: https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatic/plants/curly-pondweed

Additional Reporting Tool

EDDMapS (Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System)

Submit curly-leaf pondweed sightings for regional tracking.

Phone: (706) 542-9031

Website: https://www.eddmaps.org/

Sources APR 2025: StarTribune, MAISRC, ChatGPT

Starry Stonewort: A Growing Threat to Minnesota Lakes

Published Summer 2024

Starry Stonewort (Nitellopsis obtusa) is an invasive aquatic species that has increasingly become a concern in Minnesota's lakes.

First detected in the state in 2015, this alga-like plant, native to Eurasia, spreads rapidly, forming dense mats that can choke out native vegetation, disrupt fish habitats, and hinder recreational activities like boating and swimming. The plant is particularly concerning because of its resilience and ability to spread. Starry Stonewort primarily spreads through the fragmentation of its stems, which can easily hitch a ride on boats, trailers, and other watercraft. Once established, it forms thick, star-shaped bulbils (circled in red in picture above) that give the species its name. These bulbils allow it to survive in the sediment, making it difficult to eradicate. Efforts to control Starry Stonewort in Minnesota have included chemical treatments and mechanical removal, but these methods have proven only partially effective. The best strategy remains prevention—educating the public to clean, drain, and dry their equipment to prevent the spread from infested lakes to new bodies of water. With its rapid spread and significant impact on ecosystems, Starry Stonewort represents a serious threat to Minnesota's cherished lakes, making it crucial for continued monitoring and preventive measures.

On August 12th, six members of LICA joined Limnologist Carolyn Dindorf of Bolton & Menk, they surveyed points around the whole lake, sifting through raked up piles of vegetation from the bottom of the lake looking for Starry Stonewort and other AIS. Luckily, they did not find any Starry Stonewort at this time.

As of the most recent reports, Starry Stonewort has been confirmed in several lakes within the Twin Cities metro area. Some of the key lakes affected include:

1. Lake Minnetonka (Hennepin County) - Lake Minnetonka has had confirmed infestations of Starry Stonewort in multiple bays.

2. Medicine Lake (Hennepin County) - Located in Plymouth, this lake has also been identified as having Starry Stonewort.

3. Lake Koronis (Stearns County) - This lake is notable for being one of the first and most severe cases of infestation in Minnesota.

These lakes are closely monitored by state agencies and local conservation groups, and efforts to control the spread of Starry Stonewort continue to be a priority to protect other nearby water bodies. The presence of this invasive species in such prominent lakes highlights the importance of preventive measures, especially for boaters and anglers, to stop further spread.

Click for DNR Fact Sheet on Starry Stonewort

Signal Crayfish

First published Spring 2024

Signal crawfish have a distinctive white or turquoise patch at the claw hinge. Image courtesy rdclark via iNaturalist.

A new invasive crayfish - the Signal crayfish was found in Lake Winona, near Alexandria late last Fall. Signal crayfish are native to the Pacific Northwest but have been found in parts of California and Europe and now in Minnesota. The most distinguishing feature is a white or turquoise patch on the top at the claw hinge. Read more here at MAISRC's website.

Curly-Leaf Pondweed in Minnesota Lakes: What You Need to Know

Published Spring 2024

Curly-leaf pondweed is an invasive plant that has spread across many Minnesota lakes. It has curly, wavy leaves and can grow up to 15 feet tall.

Curly-leaf pondweed is an invasive plant that has spread across many Minnesota lakes. It has curly, wavy leaves and can grow up to 15 feet tall.

This plant can cause significant problems for the environment and recreational activities in our lakes. Curly-leaf pondweed is found in over 700 lakes across Minnesota, including Lake Independence. This widespread presence highlights the importance of management efforts to control and prevent the spread of this invasive plant.

Impact on Minnesota Lakes:

1. Ecological Impact:

Curly-leaf pondweed grows quickly and takes over areas where native plants should be. This reduces the variety of plants and animals in the lake, making it less healthy and balanced.

2. Water Quality:

When curly-leaf pondweed dies off in mid-summer, it releases nutrients into the water. These nutrients can cause algal blooms, which are rapid increases in algae. Algal blooms can make the water green and murky and reduce oxygen levels, which is bad for fish and other aquatic life.

3. Recreational Impact:

Thick mats of curly-leaf pondweed can get tangled in boat propellers, fishing lines, and make swimming unpleasant. It can cover large areas of the lake, making it hard to enjoy activities like boating, fishing, and swimming.

4. Economic Impact:

Managing curly-leaf pondweed can be expensive. The presence of this plant can also lower property values around the lake, as it makes the lake less attractive and enjoyable.

Management Strategies:

1. Mechanical Harvesting:

This involves cutting and removing the plants from the lake. It's like mowing the lawn underwater. While this can help temporarily, it needs to be done regularly to keep the plant under control.

2. Chemical Treatments:

Herbicides can be used to kill curly-leaf pondweed. These chemicals must be applied carefully to avoid harming other plants and animals. Sometimes, multiple applications are needed to be effective.

3. Biological Control:

Scientists are looking into using natural predators, like certain types of insects, to control curly-leaf pondweed. This method is still being researched and is not widely used yet.

4. Preventative Measures:

Preventing the spread of curly-leaf pondweed is crucial. Boat cleaning stations and public education campaigns help make sure boaters clean their equipment to avoid spreading the plant to other lakes.

5. Integrated Management:

Using a combination of methods—mechanical, chemical, biological, and preventative—provides the best chance of controlling curly-leaf pondweed effectively.

Future Directions:

1. Research:

Ongoing research aims to find new and better ways to control curly-leaf pondweed, including developing more effective herbicides and biological control methods.

2. Community Engagement:

Educating the public about the importance of cleaning boats and equipment can help prevent the spread of curly-leaf pondweed to other lakes. Community involvement is crucial for long-term success.

3. Policy Development:

Stronger rules and better enforcement can help limit the impact of curly-leaf pondweed. Policymakers are working to create and implement measures that protect our lakes from invasive species.

Conclusion:

Curly-leaf pondweed is a significant problem for Minnesota lakes, affecting the environment, water quality, recreation, and local economies. Managing this invasive plant requires a mix of methods, ongoing research, community involvement, and strong policies to keep our lakes healthy and enjoyable.

For more information, visit the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) website at [www.dnr.state.mn.us](https://www.dnr.state.mn.us) or contact the Minnesota DNR Invasive Species Program at invasivespecies.dnr@state.mn.us or (651) 296-6157.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) water testing to detect AIS

The Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center (MAISRC) at the University of Minnesota has pioneered a revolutionary technique in monitoring and managing invasive species: Environmental DNA (eDNA) water testing. eDNA testing offers a highly efficient and non-invasive way to detect the presence of aquatic invasive species in lakes, rivers, and streams. By collecting and analyzing water samples, MAISRC scientists can identify the DNA left behind by species, including invasive plants, animals, and pathogens, that might not be visible otherwise.

This technology is a breakthrough for early detection, which is critical in managing invasive species and protecting native ecosystems. Traditional monitoring methods can be labor-intensive, requiring frequent sampling and detailed visual surveys, but eDNA allows scientists to detect a species before it becomes established, making preventive actions far more effective. MAISRC’s eDNA testing has been used to track harmful species such as zebra mussels, Eurasian watermilfoil, and spiny water fleas.

The process begins with researchers collecting water samples from targeted locations. The DNA extracted from these samples is then amplified and compared to known invasive species DNA in the lab. If a match is found, it indicates that the species is or has recently been present in that body of water. By enabling rapid response to new invasions, eDNA testing helps lake associations, local governments, and environmental agencies respond swiftly and cost-effectively.

As MAISRC refines eDNA testing, it continues to bring invaluable insights to aquatic invasive species management, empowering local communities and conservation organizations in Minnesota and beyond. For more information check out the video webinar below.

Zebra Mussel Update

by Mike McLaughlin, LICA Board Member

Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) are an invasive, fingernail-sized mollusk that is native to fresh waters in Eurasia.They are native to the Caspian and Black Seas south of Russia and Ukraine. They are easy to identify, with a distinct, flat-bottomed ‘D’ shape to their shells that allows them to sit flat against a solid surface, and black, zigzag stripes against a cream background that earned them their name. They grow around two inches long at most, and are microscopic in their larval stage, which is known as a “veliger.” They are short-lived (between two and five years), and begin reproducing at two years of age. Each female can release up to a million eggs per year. Their name comes from the dark, zig-zagged stripes on each shell. The theory is that zebra mussels probably arrived in the Great Lakes in the 1980s via ballast water that was discharged by large eastern European ships. They have spread rapidly throughout the Great Lakes region and into the large rivers of the eastern Mississippi drainage. They have also been found in Texas, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and California. Zebra mussels negatively impact ecosystems in many ways. They filter out algae that native species need for food and they attach to--and incapacitate--native mussels. Power plants must also spend millions of dollars removing zebra mussels from clogged water intakes.

“Biofouling,” or the accumulation of adult zebra mussels on almost any surfaces put in the water, is one of the more notable impacts zebra mussels can have on a local economy. Zebra mussels are armed with rootlike threads of protein, called “byssal threads,” that allow them to firmly attach themselves to hard surfaces such as rocks, native mussels, docks or boats. Typically, this isn’t a problem for boats that are only in the water for short trips, but boats, docks or intake pipes that are left in the water for a long period of time can become encrusted and be very difficult to clean. If a boat owner also fails to drain the water from his or her motor, any veligers floating in the water will root themselves and clog the machinery as they reach adulthood.

Biofouling is a problem in the ecological world as well. Zebra mussels will attach to native mussels much like they do docks, and in large enough numbers can prevent the natives from moving, feeding, reproducing, or regulating water properly causing their local extinction. The zebra mussels also outcompete the natives for food and space, and because of their fast reproduction can quickly overwhelm a water system. Viewed up-close underwater, two tiny siphons can be seen projecting into a narrow gap between the shell valves of each animal — these siphons are used to pump water for respiration and feeding.

The feeding habits of zebra mussels can also have a drastic impact on an infested lake because of the way they siphon particles of plankton from the water. They are highly efficient at this, and a large population of mussels can quickly clear the water of almost all floating particles. They cause damage by consuming organisms like zooplankton, which can make it harder for species at higher levels of the food chain to find sufficient food. This change can cause shifts in local food webs, both by robbing food from native species that feed on plankton and also by increasing water clarity and thus making it easier for visual predators to hunt.The mussels can also promote algae blooms through this filter feeding process in which the mussels consume just some forms of algae that are beneficial to the ecosystem while refraining from eating detrimental varieties like blue-green algae.

In an effort to reduce zebra mussel populations, a paper released by the University of Minnesota in partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey demonstrated the most effective ways to eradicate the inch-long nasties, even in the icy waters of our state. Most chemicals used to exterminate zebra mussels are developed and tested in the warmer states located south of Minnesota, said James Luoma, a USGS researcher who was one of the leaders of the study. While these chemicals may work efficiently in warmer climates, they do not operate as well in the frigid waters of Minnesota lakes in the fall, he said. “A lot of these infestations are found late in the year when people are removing equipment such as docks or boats,” Luoma said. “In the past, [those treating zebra mussels] did not have the information available to [determine if] a product would be effective in cold waters.”

MAISRC, the Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center, has completed sequencing of the genome of the zebra mussel in order to isolate markers to study spread and explore possible genetic weaknesses that can be targeted for control. And now, researchers have discovered how to most efficiently kill the mussels in Minnesota lakes without overusing the chemicals. The results of the study indicate that three zebra mussel treatments have the ability to exterminate more than 90 percent of the invasive populations in water temperatures of 45 degrees Fahrenheit. EarthTecQZ, Niclosamide, and Zequanox. Niclosamide, required only 24 hours of exposure to achieve a high mortality rate while the others required longer. By using the proper amounts of these products, the researchers hope to find the “sweet spot” that kills a substantial number of zebra mussels without affecting harmless non-invasive species, said Nicholas Phelps, the director of the

The Klancke's on South Lakeshore Drive found zero mussels 2017-2019, 30 in 2020 and thousands this year as seen on these photos of a zebra mussel collecting plate they have had hanging on their dock since 2017.

University’s Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center, which funded the study. In addition to testing the concentrations on zebra mussel veligers, the researchers tested those same concentrations on snails, four native fish species, one native mussel species, and Daphnia (water flea - a zooplankton species) to see how other species would respond to this type of treatment.

“This is the first time that we’ve really created a plan that people in Minnesota can actually put into action on their lakes to control zebra mussels,” said Christine Lee, communications specialist for MAISRC. By reducing the populations of zebra mussels, the researchers hope to mitigate the species‘ negative economic impact, which can total more than one billion dollars per year nationwide, according to the U.S. Department of State.

Link to an article about how to protect your boat:

https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/invasives/fact/pdfs/ProtectYourBoat.pdf

Link to DNR’s page on zebra mussels:

https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/invasives/aquaticanimals/zebramussel/index.html

Yellow Iris are invasive

by Tom Blanck

Published Spring 2023

Last spring, my wife and I were kayaking in the channel behind Lindgren Lane. We came across a number of plants sporting beautiful yellow flowers growing right on the edge of the channel. They looked like irises and we thought someone must have gone to some trouble to plant these lovely flowers on the swampy shore. They were impressive!

Wrong! Turns out these beauties are an invasive species! Iris pseudacorus (Pale-Yellow Iris or Yellow Flag Iris) has escaped cultivation and now is spreading rapidly across parts of Minnesota. A native plant of Eurasia, it is a perennial, herbaceous, aquatic plant whose leaves and flowers grow above the water surface. It grows 2-3 feet tall along shorelines in shallow water. It forms very dense mats of rhizomes and crowds out native plant species.

The Yellow iris flower is 3 to 4 inches across with 3 large petal-like sepals that hang down and 3 smaller upright petals. The lower sepals have a ring of reddish brown flecks near the base and are beardless. There are a few flowers at the end of each stalk.

Fruit is an oblong, 3 angled capsule around 2 to 3 inches long and 1/3 to ½ as wide. Each 6-angled seed pod is about 2-4 inches long and can produce more than 100 seeds that start pale before turning dark brown. Each seed has a hard outer casing with a small air space underneath that allows the seeds to float. Yellow iris reproduces vegetatively through horizontal stems growing below the soil surface, called rhizomes, forming roots and producing new plants.

Yellow iris is poisonous to humans and animals if eaten, and its sap can cause skin irritation.

Small populations of yellow flag iris can be manually removed. Be sure to wear gloves and long sleeves, as the sap of the plant may cause skin irritation. All parts of the plants must be removed, especially the rhizomes. Cutting flower heads may help prevent the plants from spreading as quickly. Aquatic herbicides may be effective at controlling yellow flag iris, but typically herbicide use in aquatic environments requires a permit, so check with your local DNR office.

Here is a link to the MN DNR sire for more information: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/invasives/aquaticplants/yellowiris/index.html

July 23, 2021 AIS Monitoring Update

Lake Independence has know infestations of Eurasian watermilfoil, Curly-leaf Pondweed, and Zebra Mussels, all were found during our survey. Newest to our AIS list is Yellow Iris which we found last year for the first time. This year a large patch was noted by Kristen Blanck when she was kayaking near the Lindgren lane channel. Good news is we did not find any Starry Stonewart which has made appearances in other area lakes.

A big thanks to our hosts, Pat and Dick Wulff, for serving a delicious brats and sauerkraut lunch before we headed out on the water!

Craig Olson and Kristen Blanck pull in the first rake of aquatic plants to be surveyed.

Dick Wulff was our captain for the day. LICA members Craig Olson, Kristen Blanck, Pat Wulff and Barbara Zadeh went out on the water with limnologist Carolyn Dindorf from Fortin Consulting.

A pitstop at the home of Bob and Annie Ibler on Lindgren Lane to look at the many zebra mussels they have found on their shoreline, mostly attached to these native clams.

Yellow Iris may be pretty but they are an invasive plant that chokes out native plants. Look for an update coming soon with information about this newest invasive.

2019 Survey Results:

Eurasian milfoil

Curly-leaf pondweed

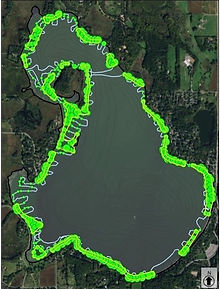

In the summer of 2019, LICA commissioned James Johnson of Freshwater Scientific Services to survey Lake Independence and identify the areas of the lake with the highest concentrations of Eurasian milfoil and curlyleaf pondweed. The curlyleaf pondweed survey was performed in late spring when the growth is peaking; the milfoil survey took place in the summer when the concentrations of milfoil are at their maximum. The data was collected by following a zig-zag course in the shallow areas all around the lakeshore. GPS readings were taken to pinpoint the exact location of each measurement.

The purpose of the survey was to identify those areas where treatment would have maximum beneficial impact. But Johnson recommended to the Board that before we take any action, we develop an Aquatic Plant Management (APM) Plan that spells out our goals and objectives, to provide guidance when prioritizing future projects. There are a number of issues related to treatment plans: cost vs benefit, input from lakeshore owners, areas where treatment would be most effective, what type of herbicide to use, etc. Before drafting our APM plan, the LICA board will be surveying members for their input. We will also be working closely with experts from the U of M, DNR and Three Rivers.

Curly-leaf Pondweed

Concentrations

Potential Treatment Areas

Eurasian Milfoil

Concentrations

Potential Treatment Areas